Imagine stepping out your front door not into a concrete canyon, but into a vibrant, green oasis. This isn’t a fantasy; it’s the attainable future of our cities, forged through the deliberate architecture of urban landscapes. This discipline moves beyond mere beautification, representing a fundamental rethinking of how we design the public realm. It is the intentional integration of built form and natural systems to create cities that are resilient, equitable, and profoundly human-centric. This guide explores the core principles and actionable strategies of this transformative field, providing a roadmap for professionals and advocates dedicated to forging a sustainable urban future.

What is the Architecture of Urban Landscapes?

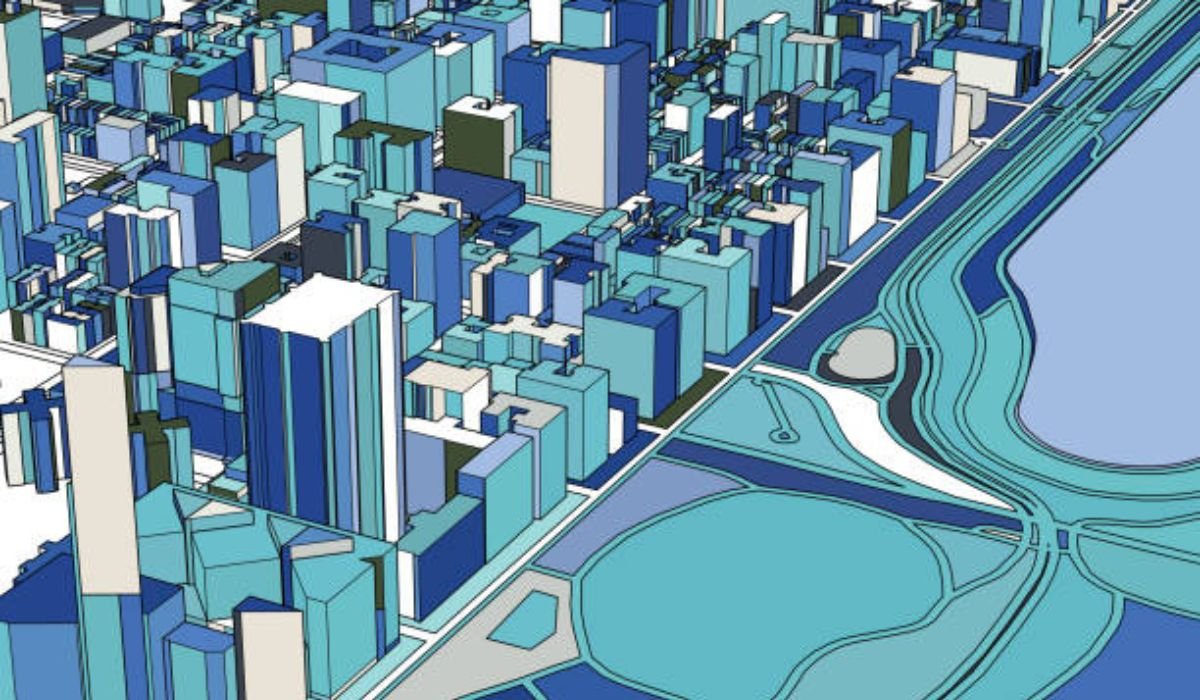

At its core, the architecture of urban landscapes is the interdisciplinary practice of designing the connective tissue of a city—its parks, plazas, streetscapes, waterfronts, and green corridors. It’s where spatial planning meets ecology, and civil engineering embraces social equity. Unlike traditional architecture focused on a single building, this field considers the vast, complex “room” of the city itself.

Think of it as choreographing the experience of urban life. It answers critical questions: How does a pedestrian move from a transit stop to their office? Where does stormwater go during a flood? How can a vacant lot become a community asset? By synthesizing hardscape elements (pavement, walls, lighting) with softscaping (trees, meadows, wetlands), practitioners create multifunctional spaces that perform essential ecosystem services like air purification, climate regulation, and habitat provision.

READ ALSO: The Future of Smart Cities: Trends & Technologies Shaping Urban Life

The Foundational Pillars of Sustainable Urbanism

Creating a successful urban landscape isn’t accidental. It rests on several interdependent pillars that guide every decision, from a city-wide masterplan to the material of a park bench.

Site Analysis: Reading the Urban Terrain

You wouldn’t build a house without understanding its lot. The same rigor applies to the city scale. Comprehensive site analysis is the critical first step, examining:

- Historical & Cultural Layers: What is the site’s story? Are there culturally significant elements to preserve?

- Environmental Conditions: Sun path, wind patterns, soil quality, hydrology, and existing flora/fauna.

- Social Dynamics: How is the space currently used (or avoided)? Who lives and works nearby? This human-centric data ensures the design meets real community needs, a cornerstone of sustainable urbanism.

Biophilic Design: Reconnecting People with Nature

Biophilic design is the practice of integrating direct and indirect experiences of nature into the built environment. Why does this matter? Because humans have an innate biological connection to nature. In urban settings, biophilic design can reduce stress, improve cognitive function, and enhance overall well-being. This is a key reason how the architecture of urban landscapes improves mental health. Implementations include:

- Direct Nature: Ample greenery, water features, habitat gardens.

- Indirect Nature: Natural materials (wood, stone), natural light and ventilation, shapes and forms found in nature.

- Space & Place: Creating prospects (open views) and refuges (quiet, sheltered spaces).

Green Infrastructure: The City as an Ecosystem

Green infrastructure is the engineered answer to environmental challenges. It involves strategically using natural systems and sustainable materials to manage resources. Instead of treating rain as waste to be piped away, green infrastructure sees it as an asset. Examples include:

- Bioswales & Rain Gardens: Vegetated channels that filter and absorb stormwater.

- Green Roofs & Walls: Insulate buildings, reduce the urban heat island effect, and provide habitat.

- Permeable Pavements: Allow water to seep into the ground, recharging aquifers.

Key Elements in the Urban Fabric

The tangible components of urban landscapes fall into two primary categories: the hard and the soft, the built and the grown. Their thoughtful integration defines the character and function of a space.

Hardscape Elements: The Built Framework

Hardscape provides structure, accessibility, and definition. Key considerations include:

- Material Selection: Using local, recycled, or low-carbon sustainable materials for the architecture of urban landscapes (e.g., reclaimed granite, recycled composite decking) reduces environmental impact.

- Spatial Definition: Walls, steps, and pavers can create intimate courtyards or grand civic plazas.

- Circulation: Well-designed pathways, ramps, and stairs ensure universal accessibility and intuitive movement.

Softscaping: The Living Layer

This is the photosynthetic heart of the landscape. Beyond aesthetics, strategic planting:

- Mitigates Climate: Tree canopies provide shade, while transpiration cools the air, directly combating the urban heat island effect.

- Manages Water: Deep-rooted plants stabilize soil and absorb runoff.

- Supports Biodiversity: Native plant palettes create corridors for pollinators and urban wildlife, integrating nature into the architecture of urban landscapes at a fundamental level.

Overcoming Urban Challenges Through Design

Modern cities face unprecedented pressures. The architecture of urban landscapes provides a proactive, design-led toolkit for resilience.

Combating the Urban Heat Island Effect

The urban heat island effect, where cities become significantly warmer than their rural surroundings, is a major health and energy concern. Landscape architecture counters this by:

- Maximizing the tree canopy for shade.

- Specifying light-colored, reflective paving materials.

- Incorporating water features that cool through evaporation.

- Replacing dark, heat-absorbing surfaces like asphalt with vegetated areas.

Designing for Social Cohesion and Mental Health

The public realm design is our shared living room. Its quality directly impacts community health. Successful spaces foster interaction and provide respite. This includes designing inclusive playgrounds, quiet contemplative gardens, and vibrant, activated plazas that welcome people of all ages and backgrounds. The importance of architecture of urban landscapes in modern cities is clearest here—it directly shapes social capital and collective well-being.

The Future of Urban Landscapes

The field is dynamic, driven by technological innovation and urgent climate imperatives. Future trends in the architecture of urban landscapes point toward even deeper integration and intelligence.

- Data-Driven Design: Using sensors and IoT to monitor soil moisture, foot traffic, and microclimates, allowing for responsive, adaptive management.

- Climate-Adaptive Design: Creating landscapes that are not just “green” but are specifically engineered for flood resilience, drought tolerance, and carbon sequestration.

- Equity-Centered Planning: Prioritizing investments in historically underserved neighborhoods to ensure all citizens benefit from green space—a concept known as “green justice.”

- Urban Regenerative Design: Moving beyond sustainability to designs that actively restore ecological health and community wealth.

From Vision to Reality: A Call to Action

The architecture of urban landscapes is not a luxury; it is essential infrastructure for the 21st-century city. It requires a collaborative effort—urban planners crafting supportive policy, landscape architects designing with ecological literacy, municipal developers championing quality, and community advocates voicing their needs.

The blueprint for better cities is written in the language of parks, streets, and plazas. It calls for designs that cool our streets, shelter our communities, nourish our biodiversity, and uplift our spirits. The task ahead is to move from isolated projects to a connected, city-wide ecosystem. Let’s build cities that don’t just exist on the land, but thrive with it.

Begin your next project with a landscape-first mindset. Conduct a community visioning session, advocate for robust green infrastructure policy, or explore a certification like SITES to benchmark your sustainable design. The future city is waiting to be grown.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE: Green Infrastructure and Sustainable Urban Design: The Planner’s Guide to Urban Resilience